Loops

So far our programs have not used any loops. A loop is a repetition of some section of code. Loops are essential in the common situation where user input or data determines how many times something should occur. In other cases, the programmer just wants to save time by reducing the amount of typing or copy-pasting required, as our first example below shows.

Consider the simple example of the “bottles of beer” song. This is how it goes (as far as I know):

99 bottles of beer on the wall, 99 bottles of beer, take one down, pass it around, 98 bottles of beer on the wall.

98 bottles of beer on the wall, 98 bottles of beer, take one down, pass it around, 97 bottles of beer on the wall.

97 bottles of beer on the wall, 97 bottles of beer, take one down, pass it around, 96 bottles of beer on the wall.

…

1 bottle of beer on the wall, 1 bottle of beer, take it down, pass it around, no more bottles of beer on the wall.

Clearly this is a loop. (But a program that prints these lyrics need

not use loops, since you know it should print 100 lines. You could

just use 100 separate cout statements. Using a loop, on the other

hand, saves us from such tedium.)

loop n. The frantic rehearsal of a certain sequence of program steps until the system “gets it right,” failing which the loop is branded endless; the repetition of a certain sequence of program steps

while, and only while, a set of unforeseen circumstances prevails; an algorithmic recycling; a piece of code in search of a loophole. – The computer contradictionary

Building up to 99 bottles of beer

In C++, the simplest loop is the while loop. Here is a while loop

that prints the first line of the song, forever and ever

(infinitely-many copies of this same lyric are shown on the screen):

while(true)

{

cout << "99 bottles of beer on the wall... "

<< "pass it around, 98 bottles..."

<< endl;

}The general format for a while loop is:

while(conditional)

{

// do stuff...

}where conditional is the same kind of conditional used in if

statements. In other words, conditional must be something that is a

bool result.

In an if statement, there is no repetition, so the conditional is

only checked once. In a while loop, on the other hand, the

conditional is checked before the loop begins and after every time the

stuff inside the loop is executed. In other words, first conditional

is checked. If it turns out to be true, then stuff... is

executed. Then conditional is checked again. If it is true,

stuff... is executed. And so on, looping over and over so long as

conditional is true. If at some point conditional is false, then

stuff... is not executed and the loop is finished. Execution resumes

after the while loop block (a block starts with { and ends with

}).

We saw a “degenerate” loop earlier. It started with while(true). A

loop like that never stops because the conditional is always

true. Another degenerate case is while(false). In this case, since

the conditional is never true, the stuff inside the block never

executes. We will see later that while(true) actually can be useful

in a program, but while(false) is never useful.

A program without a loop and a variable isn’t worth writing. – Alan J. Perlis, Epigrams on Programming

A loop can be stopped by two techniques. The first technique will be discussed now. A loop stops when the conditional is false. Consider this loop:

while(x != 0)

{

// do stuff...

}This loop is stopped only when x == 0 because that is the only case

when the conditional is false. This suggests that somewhere inside the

loop, x has to change such that, eventually, x is given the value

0. If that never happens inside the loop, the loop never ends.

Consider the bottles of beer again. Here is a loop that mostly works:

int n = 99;

while(n > 0)

{

cout << n << " bottles of beer..."

<< "take one down..."

<< (n-1) << " bottles of beer..."

<< endl;

n--;

}See how in that case, the conditional n > 0 does eventually become

false, because n is decreased each time the loop executes.

In the last code segment, the final bottles-of-beer lyric is not handled properly. Here is a fix:

int n = 99;

while(n > 1)

{

cout << n << " bottles of beer..."

<< "take one down..."

<< (n-1) << " bottles of beer..."

<< endl;

n--;

}

cout << "1 bottle of beer ..." << endl;The last case, when n == 1, is special so we put it outside the loop.

What’s really happening

The while() loop is basically converted into an if and goto

statement. For example, this loop:

int x = 0;

while(x < 10)

{

cout << "blah";

x++;

}becomes this code:

int x = 0;

CHECK: // name this line of code "CHECK"

if(x < 10)

{

cout << "blah";

x++;

goto CHECK; // here is the "loop" action

}loophole n. 1 The escape route sought by a loop. 2 Metacomputer science The conceptual gap left when a loop migrates to > another part of the metasystem. Any fresh loop nearby will be *attracted into > the hole, and so on. – *The computer *contradictionary

Interactive program

The following program repeatedly asks the user for a letter; if the user ever types “q” then the program is done.

char c;

cout << "Enter a letter, 's' to skip the message,"

<< " 'q' to quit: ";

cin >> c;

while(c != 'q')

{

if(c != 's')

{

cout << "You typed " << c << endl;

}

cout << "Enter a letter, 's' to skip the message,"

<< " 'q' to quit: ";

cin >> c;

}This program is better written with a do-while loop because we want

the cout and cin pair to be done even before the check. Here it is

with do-while:

char c;

do

{

cout << "Enter a letter, 's' to skip the message,"

<< " 'q' to quit: ";

cin >> c;

if(c != 's' && c != 'q')

{

cout << "You typed " << c << endl;

}

} while(c != 'q');for() loop

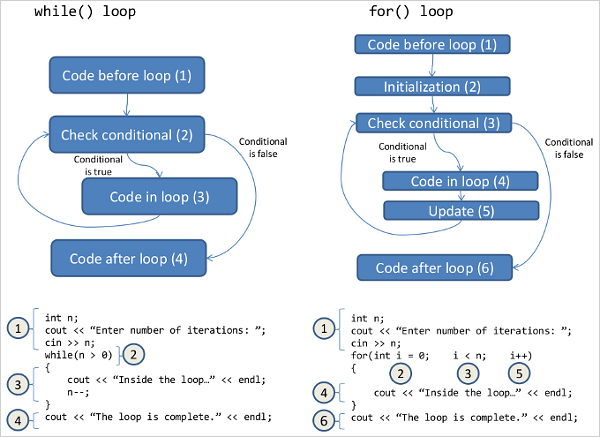

Anything a while loop can do, a for loop can do, and vice

versa. However, each kind of loop is used equally often in practice

because they have slightly different “styles.” First, we will look at

how for loops work.

This is the basic structure of a for loop:

for(initialization; conditional; update)

{

// do stuff...

}This is what the three parts inside the parentheses (commonly) mean:

-

initialization– create counting variables and set their values -

conditional– determine if the loop should repeat; this conditional usually refers to a variable defined in theinitialization -

update– commonly used to change a variable defined in theinitializationand referred to in theconditional; changing this variable should eventually cause the conditional to be false, causing the loop to complete

for loops follow this sequence of steps:

-

execute whatever is put in the

initialization -

check the

conditional; if it evaluates tofalse(0) then skip the loop; if it evaluates totrue(any integer not equal to0), continue to the next step -

execute the

stuffinside the block -

execute the

update -

go to step 2

It’s useful to see how a while loop can be converted to a for

loop. In this example, the while loop and the for loop are

(nearly) equivalent:

int i = 0;

while(i < 10)

{

// do stuff...

i++;

}

for(int i = 0; i < 10; i++)

{

// do stuff...

}(The two are only “nearly” equivalent for the following reason: in the

while loop case, the integer i is declared outside of the loop, so

code that follows the loop block can still refer to i. In the for

loop case, the integer i can only be used inside the for loop

block; it does not exist when the loop is finished.)

Let’s dissect that for loop above:

-

initialization:int i = 0 -

conditional:i < 10 -

update:i++

You should be able to see these same three components present in the

while loop, but the while loop does not have special handling of

the three components. On the other hand, a for loop is specifically

designed to have exactly those three components (initialization,

conditional, and update).

A for loop need not have anything in any of the three components. If

none of the components have code in them, it is equivalent to an

infinite loop. In other words, these two loops are equivalent:

while(true)

{

// do stuff forever... (or until "break" is encountered)

}

for(;;)

{

// do stuff forever... (or until "break" is encountered)

}Here is the bottles-of-beer example again, this time using a for

loop:

for(int n = 99; n > 1; n--)

{

cout << n << " bottles of beer..." << "take one down..."

<< (n-1) << " bottles of beer..." << endl;

}

cout << "1 bottle of beer ..." << endl;Here is an example that is equivalent to Σ100j=1 Σ100k=1 (j+k)^2

int sum = 0;

for(int j = 1; j <= 100; j++)

{

for(int k = 1; k <= 100; k++)

{

sum += (j+k)*(j+k);

}

}Here is an example that prints a triangle of stars:

// the maximum width of a line of stars

int width = 30;

// print 2 stars, then 4 stars, etc., centered on the line

for(int i = 2; i <= width; i += 2)

{

// we want to print "i" stars in the middle of the line,

// so we need to add spaces before the stars, then print

// the stars (we don't need spaces after the stars, just

// a newline)

// print spaces

for(int j = 0; j < ((width - i) / 2); j++)

{

cout << " ";

}

// print stars

for(int j = 0; j < i; j++)

{

cout << "*";

}

// print newline

cout << endl;

}Here is the result:

**

****

******

********

**********

************

**************

****************

******************

********************

**********************

************************

**************************

****************************

******************************

Let’s fix that extra blank line at the bottom. We will check if the loop is on the last iteration; if it is, we don’t print the last line:

// the maximum width of a line of stars

int width = 30;

// print 2 stars, then 4 stars, etc., centered on the line

for(int i = 2; i <= width; i += 2)

{

// we want to print "i" stars in the middle of the line,

// so we need to add spaces before the stars, then print

// the stars (we don't need spaces after the stars, just

// a newline)

// print spaces

for(int j = 0; j < ((width - i) / 2); j++)

{

cout << " ";

}

// print stars

for(int j = 0; j < i; j++)

{

cout << "*";

}

// print newline only if we aren't on the last line

if(i != width)

{

cout << endl;

}

}Notice that in each of these examples, we are doing stuff some

particular number of times (the number of times is already known, like

100, or stored in an integer or a calculation, such as ((width - i)

/ 2)). These are the typical use cases for the for loop.

Diagram of while() loop and for() loop

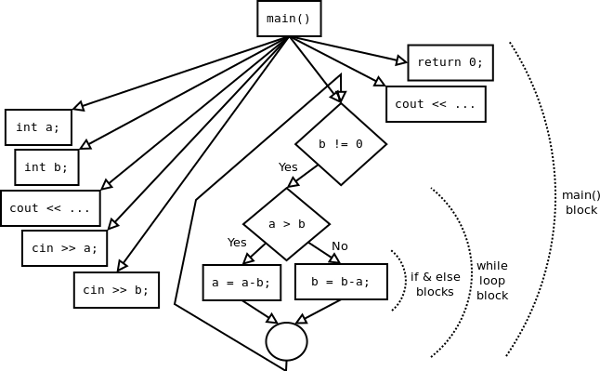

Diagram of nested blocks

When we use blocks in if and else and while and for (recall

that blocks begin and end with { and }), we are creating nested

structures (blocks inside blocks). We can visualize this with a

diagram of the following program:

// This program finds the greatest common divisor (gcd)

// of two integers a & b, using Euclid's method.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

int a;

int b;

cout << "Enter a and b: ";

cin >> a;

cin >> b;

while(b != 0)

{

if(a > b)

{

a = a - b;

}

else

{

b = b - a;

}

}

cout << "GCD is " << a << endl;

return 0;

}

In the diagram, computation proceeds left-to-right; if there is no right branch, computation proceeds at the parent’s next branch.

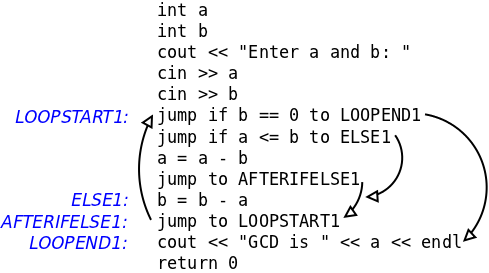

This is what the same program looks like to the computer (in “assembly” code or “machine” code, more or less). Notice all the jumps, which are needed when the nested structures are turned into linear structures. Also notice the critical “back arrow” which produces looping behavior.

This “jumping” behavior can be achieved in C++ code using the goto

command. I’m not going to recommend that you use goto in your code,

ever. It’s highly frowned-upon because code with many jumps or goto

commands is hard to understand. It produces “spaghetti code,” which

means that if you look at any single line of code, you’ll have a hard

time figuring out under what circumstances that line of code is

executed. (This is like spaghetti, really: pick a spot in the middle

of some noodle and try to trace back to the noodle’s beginning or

end.)

For more information, read the classic Go To Statement Considered Harmful.

Self-practice: FizzBuzz

Write a program that prints the numbers from 1 to 100. But for multiples of three print “Fizz” instead of the number and for the multiples of five print “Buzz”. For numbers which are multiples of both three and five print “FizzBuzz”.