Introduction

This class is about C++, but what I want to emphasize throughout the course is that the real take away lessons have little to do with C++. What I really want you to learn is how to approach programming problems, how to approach programming languages, and how to “think like a computer.” I would call this “computer literacy.” English literacy classes ask you to read Shakespeare, Milton, Tolstoy, etc. not so much because those writers describe the world as it is today, but rather because they describe “the human condition.” Likewise, we learn C++ not simply because C++ may be useful to you, but moreso to get a sense of computation, algorithmic thinking, and problem solving. Some other programming language could be substituted and we could learn the same lessons. Why C++ has been chosen is a mixture of historical, political, and practical reasons that are really not our concern.

In many real-world situations, several programming languages are used to attack a problem. I’ll give you a few examples.

In Summer 2011, my friend interned with an organization that developed a system which crawls the web, searching for and classifying news related to artificial intelligence. The system is written in several independent modules and several different programming languages:

- Python – majority of the code; this is the artificial intelligence code

- PHP – the website

- Perl – text processor (building a training corpus)

- Shell – automation (weekly execution of the system)

- R – data analysis

- Javascript – website interactivity

- SQL – database access

This mix of languages is not atypical.

- An engineer may use one or more of the following languages in practice: Matlab, Mathematica, R, AutoLISP, FORTRAN, C, C++, Java, Python, and C#.

- A high-frequency/algorithmic trader in the financial market may use C++, Java, K, or OCaml.

- A modern platform game would be written in C++, Lua, and company-specific languages.

- A modern website may be written in PHP, Ruby, C#, Javascript, SQL, and possibly other languages.

- Research in artificial intelligence typically involves coding in Common Lisp, Prolog, Scheme, Java, and/or Python.

And so on.

It’s not about the language

The point is that which programming language you learn first, or second, or third, is not as important as learning computer literacy. If you’re literate, you’ll learn a different programming language very quickly; the language is no longer a barrier, and you can choose the right language for the job.

As it happens, most of those languages listed above are very similar to C++. So learning C++ gives you a certain advantage.

Finally, to be sure, C++ is enormously popular. A “chief steward” of the C++ ecosystem recently stated that many major applications are written in C++.

Apple’s Mac OS X, Adobe Illustrator, Facebook, Google’s Chrome browser, the Apache MapReduce clustered data-processing architecture, Microsoft Windows 7 and Internet Explorer, Firefox, and MySQL–to name just a handful–are written in part or in their entirety with C++.

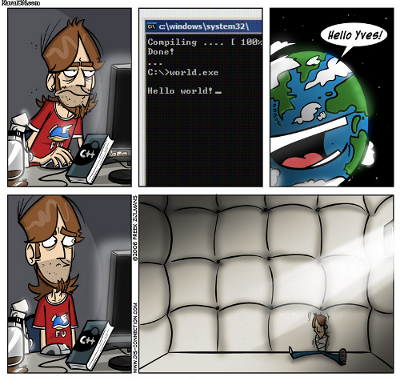

Hello, world!

It is standard practice that the first program you write in a new programming language should simply print the message “Hello, world!”

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

cout << "Hello, world!" << endl;

return 0;

}A second C++ program

Now with that out of the way, here is a slightly more useful program that computes the area of a rectangle.

// rectangle_area.cpp

// Compute the area of a rectangle.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main() {

int length, width, area;

length = 12; // length in inches

width = 6; // width in inches

area = length * width;

cout << "Area of a rectangle with ";

cout << "length = " << length << " and width = " << width;

cout << " is " << area;

return 0;

}When this program is run, the computer screen will display

Area of a rectangle with length = 12 and width = 6 is 72

We’ll discuss most of that code in the following sections of these notes.

Aside: Why return 0 at the end? Since we’re talking about computers

here, your program is executed by another program (even though perhaps

you, as a user, asked for your rectangle program to be executed). That

other program is the “shell” or your editor or whatever. The program

that executes your program may want to keep track of whether or not

your program finished successfully, or if it instead encountered an

error. Because the main() function is always where your code begins,

it’s also where your code ends, and thus is the perfect place to send

back information about whether your program completed successfully or

not. By convention, if your main() returns the value 0, then your

program was successful. Any other value means your program had an

error – it’s up to you to decide what the other possible values mean.

Every program is a part of some other program and rarely fits. – Alan J. Perlis, Epigrams on Programming

Comments

Text that follows two double slashes (//) is known as a comment.

Comments do not affect how a program runs. They are used to explain various aspects of a program to any person reading the program.

The previous program has four comments; the first gives the name of the file containing the program, and the second briefly describes what the program does. The other two comments say that the measurements are in inches.

“include” statements

An #include statement is a “compiler directive” that tells the

compiler to make a specified file available to a program. For example,

in both of these programs, #include <iostream> tells the compiler to

include the iostream file, which is needed for programs that either

input data from the keyboard or write output on the screen.

#include <xyz> literally causes the file xyz (whichever file that

happens to be) to be copied-and-pasted (included) in place of the

directive #include <xyz>. We put the include directives at the top

of our code files so that those “included” files are pasted at the top

of our code. The files we are including typically have definitions of

functions and so on, which need to appear at the top of our code.

Namespaces

using namespace std; – this line informs the compiler that the

files to be used (from the “Standard” library, brought in by the

“include”) are in a special region known as the namespace std. A

namespace is just a name attached to a large amount of code, to keep

things organized especially as programs get very large and spread

across several teams and organizations.

The “main” function

Our program consists of an int function called main. We can think

of this function as the main control center for program execution.

Every program must have a function called main. When any program

written in C++ is started, the main function is activated. No other

functions are activated unless they are activated from main or some

other function that main has activated, etc. It all begins in

main.

The body of main is enclosed in curly braces and has a final

statement: return 0; which signifies the completion of the function

and returns control back to the operating system (i.e., the program

quits when the “return” in main is reached).

What happened in the second program?

The statement int length, width, area; creates three named int

(integer) memory cells (“variables”) with no specific initial values.

The statement length = 12; assigns the value 12 to the memory cell

named length. Likewise, the statement width = 6; assigns 6 to the

cell named width.

The statement area = length * width; gets the contents of the memory

cells named length and width, then multiplies these two values and

stores the result in the memory cell named area.

The cout (pronounced “see-out”) statements produce the output that

appears on the computer screen.

The return 0; statement returns control of the program back to the

computer’s operating system.